High-Risk Patient Management Did Not Drive Early ACO Cost Savings

Spending on low- and high-risk patients dropped at the same rate among early MSSP ACOs, indicating high-risk patient interventions did not lead to early cost savings.

Source: Thinkstock

- Care coordination and care management strategies focused on high-risk and chronically ill patients did not drive early cost savings among accountable care organizations (ACOs) in the Medicare Shared Savings Program (MSSP), a recent Health Affairs study uncovered.

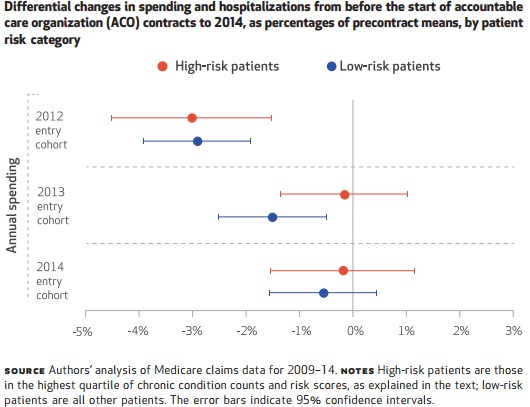

Researchers from Harvard Medical School found that ACOs that entered the MSSP in 2012 significantly lowered spending on high-risk patients in absolute terms compared to spending on low-risk patients. Costs fell $686 per beneficiary for high-risk patients versus just $207 per beneficiary for low-risk patients.

However, the cost savings were similar in relative terms, researchers found using Medicare claims and enrollment data from 2009 to 2014. Compared to pre-ACO contract spending, the MSSP ACOs launching in 2012 decreased spending on high-risk patients by 3 percent and spending on low-risk patients by 2.9 percent.

Source: Health Affairs

Furthermore, differential decreases in spending among ACOs joining the MSSP in 2013 primarily stemmed from cost savings for low-risk patients.

“While targeted efforts to enhance outpatient and preventive care for high-risk patients might have contributed to lower spending for the high-risk group, the proportionally similar spending reductions for both high- and low-risk patients are also consistent with efforts to limit service use among all patients,” researchers argued. “Such efforts could target specific services (such as post-acute care) rather than specific patients but nevertheless affect high-risk patients more per patient in absolute terms because they use more services.”

READ MORE: Good Data, Better Value-Based Care Can Boost Population Health

They also noted that improved care management infrastructure for high-risk patients may have resulted in spillover effects on low-risk patients.

MSSP ACOs may also have used different risk stratification methods to determine who their high-risk patients were. However, researchers explored if care coordination and care management strategies targeting high-risk patients reduced costly hospitalizations.

“If care management efforts by ACOs in the MSSP produced savings that were substantial but not concentrated among the high-risk patients in our study because the ACOs used less sophisticated methods than we did for identifying high-risk patients, we would still expect to see reductions in hospitalizations for ambulatory care–sensitive conditions, given that these conditions are a widespread focus of ACOs—a focus encouraged by the quality measures in ACO contracts—and heavily concentrated among high-risk patients,” researchers wrote.

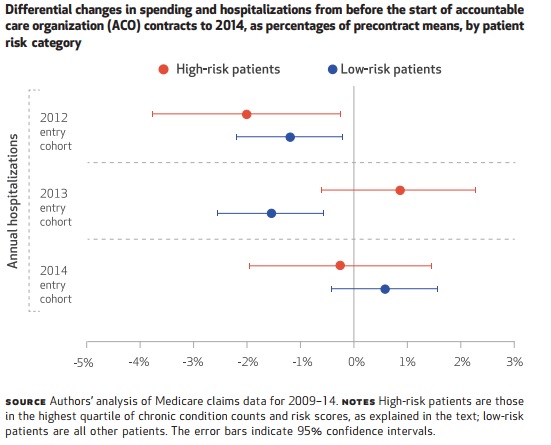

But MSSP participation was not associated with hospitalization reductions for ambulatory care-sensitive conditions, including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, congestive heart failure, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes.

ACOs that joined the MSSP in 2012 did significantly reduce hospitalizations for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma by 0.5 percentage points.

READ MORE: For Ongoing ACO Shared Savings, Look Outside Inpatient, Primary Care

However, hospitalization rates increased by 0.5 percentage points for congestive heart failure patients and 0.7 percentage points for cardiovascular disease and diabetes patients.

Source: Health Affairs

ACOs in the 2013 and 2014 MSSP cohorts did not experience changes in patients hospitalized for the studied conditions.

“These findings are consistent with care coordination and management efforts, on average, either having minimal effects on the risk of hospitalization or acting to increase the use of inpatient care by improving access and filling gaps in care for high-needs patients—at least enough to offset any reductions in hospitalizations achieved for these patients through the prevention of complications and exacerbations,” the study stated.

Researchers also noted that the increase in hospitalizations for some ambulatory care-sensitive conditions could prove that using these admissions as a sign of ambulatory care quality is inappropriate.

Overall care ratings and access to care reported by chronically ill patients improved under Medicare ACO programs, a 2014 New England Journal of Medicine study showed. The chances that increased hospitalization rates for some ambulatory care-sensitive conditions represented worsening care quality is unlikely.

READ MORE: Accountable Care Organizations Grow, But Face New Challenges

The increase in admissions may have actually reflected care quality improvements for chronically ill patients, researchers stated.

The study’s findings have several implications for ACO payment policies. First, ACO payments should account for improvements in patient experience, clinical outcomes, and structural measures of practice transformation rather than utilization-based measures, such admission rates for ambulatory care-sensitive conditions.

Payers should also separate incentive payments for quality improvement from realizing cost savings, researchers suggested. MSSP only rewards ACOs for quality improvement if the organization also realizes sufficient cost savings.

ACO incentive payments should reward organizations for quality improvement activities that do not necessarily result in significant cost savings or slight increases in utilization as long as clinical outcomes and patient experience improve.

Redesigning ACO payments to recognize quality improvements that do not generate substantial savings should particularly benefit primary care providers in ACOs. Since high-risk patient and specific condition care management programs may not significantly reduce costs for the ACOs, organizations may not be adequately compensating their primary care providers even though the programs improve care quality.

“Thus, in assessing ACO performance in the MSSP, a greater focus on patients’ experiences and outcomes that are not based on utilization could better reward physicians’ efforts or better support the implementation of practice models that improve care without placing additional demands on primary care physicians’ time,” the study stated.