OIG Testimonies Examine 340B Savings and Medicare Fraud

- The Office of the Inspector General (OIG) recently posted written testimonial on 340B savings and Medicare fraud, as submitted to the House of Representatives from Ann Maxwell, Assistant Inspector General of the OIG Office of Evaluation and Inspections, and Gary Cantrell, Deputy Inspector General for Investigations in the OIG Office of Investigations.

An Overview of Maxwell’s Testimony

As stated in Maxwell’s testimony from March 24, 2015 to Chairman Joe Pitts (R-PA), Ranking Member Gene Green (D-TX), and Subcommittee members, OIG recommends further improving and examining the 340B program by increasing transparency and clarifying rules. Such savings, says Maxwell, means Federal Resources could reach more eligible patients and provide more widespread services.

HRSA estimated that annual savings of the 340B program in 2013 was $3.8 billion, the testimony confirms.

Congress enacted section 340B of the Public Health Service Act (PHS Act), in 1992 to establish the 340B program to generate savings for certain safety net healthcare providers by allowing the purchase of cost-effective outpatient drugs.

As of February 28, 2015, 11,180 providers were participating in the 340B program, the written testimony states.

OIG’s efforts throughout the past decade to ensure the Health Resources and Services Administration’s (HRSA’s) oversight of the 340B program, revealed shortfalls, explains Maxwell. Flaws include inaccurate information about those providers eligible for discounted prices and a lack of system monitoring to ensure the correct prices were being charged to 340B providers.

OIG recommends the need for more transparency in both 340 ceiling prices and Medicaid claims for 340B-purchased drugs. OIG determined this transparency deficiency is negatively affecting 340B providers, State Medicaid programs, and drug manufacturers as there is no guarantee payments made to purchase 340-B drugs are correct.

A lack of transparency also limits states’ efforts to prevent duplicate discounts, says Maxwell.

“In 2010 over half of States had developed alternatives to the Medicaid Exclusion File, and many cited inaccuracies in the Medicaid Exclusion File as a reason for doing so,” says Maxwell.

340B providers do not have access to ceiling prices and have been overcharged before, says Maxwell’s testimonial.

“14 percent of drug purchases under the 340B program in June 2005 exceeded applicable ceiling prices,” states Maxwell. “340B providers overpaid by a total of $3.9 million during that month.”

Because states are unable to instigate automated, prepayment edits to enforce established Medicaid policies to pay for 340B-purchased drugs at 340B providers’ actual acquisition cost, they conduct costly audits and post-payment reviews to ensure payments are correct.

Therefore, OIG recommends HRSA share 340B ceiling prices with 340B providers and state Medicaid agencies, Maxwell’s testimony states.

OIG further recommends HRSA improve tools and guidance to help states and drug manufacturers identify which Medicaid claims received the 340B discount.

HRSA’s current patient definition guidance does not consider contract pharmacy arrangements’ complexity, which can lead to variation in eligibility determinations across providers and inconsistencies regarding benefits for uninsured patients.

OIG suggests the 340B program rules require further clarification. Refining HRSA guidance on patient definition as it applies to different prescription-level transactions could improve program integrity and address challenges arising from different interpretations, says Maxwell’s testimony.

Further guidance how 340B discounts should apply to uninsured patients at contract pharmacies is needed.

In June of 2015, HRSA plans to issue wide-ranging 340B program guidance to address patient definition and contract pharmacy issues.

An Overview of Cantrell’s Testimony

As stated in Cantrell’s testimony from March 24, 2015 to Chairman Peter Roskam (R-IL), Ranking Member Gene Lewis and Oversight Subcommittee members, Fraud in Medicine, Medicare spending in 2013 totaled $583 billion. The program served 52 million aged and disabled individuals.

Protecting those beneficiaries and Federal spending integrity is of utmost importance, says Cantrell’s written testimony.

As mentioned in last week’s RevCycleIntelligence.com article, OIG, HHS, and the Department of Justice (DOJ) returned $7.70 for every $1 invested in the Health Care Fraud and Abuse Control Program (HCFAC) and more than $27.8 billion to the Medicare Trust Fund since HCFAC’s inception in 1997, the testimony confirms.

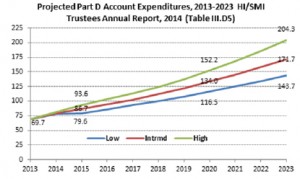

Prescription drug use is a national problem that requires immediate addressing, says Cantrell. Medicare Part D spending for drugs totaled $69.7 billion in 2013. This number, which is expected to increase to $171.7 billion by 2023, means strong program integrity and enforcement efforts need immediate implementing, says Cantrell.

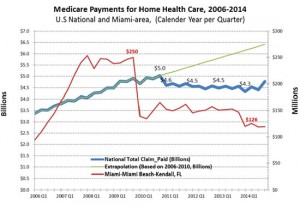

Data-driven efforts are responsible for sharp declines in Medicare payments and payments for fraud-prone healthcare services, says Cantrell.

“Our criminal prosecutions and monetary recoveries have increased, while we have seen a measurable decrease in payments for certain fraud-prone health care services,” Cantrell confirms.

Medicare payments for home healthcare decreased nationally by over $250 million per quarter – over $1 billion annually.

“If a fraud scheme is successful and continues uninterrupted, criminals will duplicate the scheme, even if the original criminal mastermind has moved to another area,” maintains Cantrell. “OIG and other program integrity partners diligently track fraud migration of both types and respond as needed to the constantly evolving landscape of health care fraud.”

Medicare fraud is often perpetuated by complex criminal networks. Such groups pose an enormous threat to the integrity of the Medicare trust funds because they intend to steal as much as possible as quickly as possible.

OIG recommends the following program integrity improvements to help prevent Medicare fraud:

• CMS should restrict certain Part D beneficiaries to a limited number of pharmacies or prescribers.

• CMS should require Medicare Part C (Medicare Advantage) and Part D plan sponsors to report fraud and abuse incidents.

• CMS should enhance its oversight mechanisms to improve compliance with the home health “face-to-face” requirement.

• Social Security Numbers on Medicare Cards: Removing Social Security numbers from Medicare cards is one step that would help protect the PII of Medicare beneficiaries.

Protection of the Medicare program and its beneficiaries is essential to the stability of the healthcare industry. OIG’s ongoing efforts in data analytics aims to address specific resources for maximized results.