Limited Quality Benefits for Early Pay-For-Performance Adopters

Clinical process scores and mortality rates were similar for early and later adopters of Medicare pay-for-performance programs, a study showed.

Source: Thinkstock

- The impact of hospital pay-for-performance models, such as Medicare’s Hospital Value-Based Purchasing Program (HVBP), have been “limited and disappointing” over the past decade, researchers stated in a new BMJ study.

The analysis of national Medicare claims data from 2003 to 2013 for over 1,100 hospitals showed that clinical process scores and 30-day mortality rates were not better at hospitals that had been participating in Medicare pay-for-performance programs for at least a decade than at hospitals that had just adopted the models.

The HVBP and its predecessor, Medicare’s Hospital Quality Incentive Demonstration (HQID), incentivized hospitals to improve clinical process scores, which assessed whether providers delivered recommended care to patients with a particular condition.

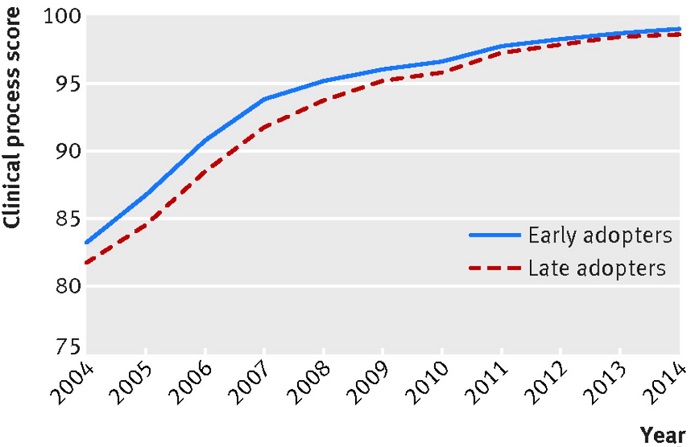

Early adopters of HQID started from modestly higher baseline clinical process scores in 2004, with an average score of 91.5 percent versus 89.9 percent for late adopters.

However, early adopters improved clinical process scores at a slow rate during the demonstration. Average scores only improved by 0.21 percent during the HQID period, which ran from 2003 to 2009.

Early adopters ended up performing at a slightly higher level than late adopters by the pre-HVBP period, but the difference between the cohorts was just 0.55 percent.

By the time the HVBP launched in 2011, early and late adopters of pay-for-performance programs did not have significantly different clinical process scores.

Source: The BMJ

The scores also reached a ceiling during the HVBP. The clinical process scores of early and late adopters reached approximately the same level by 2014, with an average score of 98.5 percent for early adopters and an average score of 98.2 percent for late adopters.

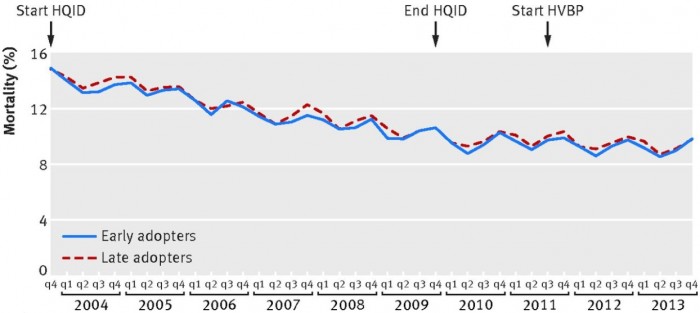

Hospitals that engaged in pay-for-performance programs early on also did not report significantly better 30-day mortality rates than late adopter hospitals during the study period, the analysis revealed.

Both hospital groups started from similar baselines. The baseline was 14.9 percent for early adopters and 14.8 percent for late adopters in the last quarter of 2003.

The groups ended at the same rate of 9.9 percent in the final quarter of 2013.

Source: The BMJ

“This suggests that the HQID did not have a meaningful effect on mortality through 2013, even though the hospitals had a decade of experience and volunteered to participate in the demonstration,” researchers wrote.

The study demonstrated that time may not help providers improve performance in value-based reimbursement models with small financial incentives.

Stakeholders have argued that providers realize greater quality and cost improvements under value-based reimbursement models the longer they participate. For example, CMS reported that accountable care organizations (ACOs) that participated in the Medicare Shared Savings Program (MSSP) longer reduced their costs more than less experienced MSSP ACOs.

About 42 percent of MSSP ACOs that started the program in 2012 saved beyond their financial benchmark in 2015 compared to only 37 percent of 2013 starters, 22 percent of 2014 starters, and 21 percent of 2015 starters.

More mature MSSP ACOs also improved their quality scores, with 91 percent of organizations in their second and third performance years earning Quality Improvement Reward points in 2015 for at least one quality measure domain.

While time seems to be the key to ACO improvement, the financial incentives in pay-for-performance programs may not be enough for even time to help hospitals improve. The HVBP, for instance, reduces a hospital’s Medicare reimbursement by 2 percent and hospitals can recoup a portion or all of the withdrawn funds by demonstrating high care quality.

In addition, the financial incentives only apply to a small set of conditions. Hospitals generate revenue from a wide range of payers. The modest adjustment from Medicare may not have been enough to motivate clinical process changes.

Program complexity also may have contributed to the limited impact of pay-for-performance programs, researchers explained. The HVBP and HQID assessed hospitals on either a range of quality measures and domains or a range of conditions.

“The current structure includes numerous measures that are difficult to track and measure by hospital leaders, and therefore, hard to improve,” researchers wrote.

Pay-for-performance programs that targeted a smaller range of quality measures or conditions better incentivized hospitals to improve care quality. For example, the Medicare Hospital Readmission Reduction Program targets hospital readmissions by reducing Medicare reimbursement for hospitals with excessive rates. The program resulted in reduced rates within a year after implementation, CMS data showed.

To ensure the pay-for-performance programs improve care quality, policymakers should consider including greater financial incentives and fewer quality measures, the study concluded.